ON THE SHOULDERS OF DEAD GIANTS

Triple-A horror is dead. Long live indie horror. Or at least, that’s the sentiment I’ve seen floating around the net, especially after the recent tepid reception of The Callisto Protocol. I can’t confirm the death of triple-A horror since I don’t have a machine that could run Callisto. It seems… fine, though its parade of ash-white humanoid enemies leaves something to be desired. Certainly Capcom and Konami are hoping there's life in the genre, with both releasing remakes of some of their most celebrated horror games (Resident Evil 4 and Silent Hill 2) in 2023. Ok, so maybe not dead, but the prevalence of remakes and “spiritual successors” suggest some stagnation. Resident Evil 4 getting a remake after Resident Evil: Village already riffed so heavily on it feels a little desperate. So does Konami announcing five separate Silent Hill projects after years of selling out its IP for pachinko machines to ever-diminishing returns. Indie horror, though? Well, there’s certainly a lot of it. I’ve said my piece on the loud chase-em-ups in HORROR.COM, so this time I’d like to focus on three games from this year I enjoyed, but which are heavily inspired by horror legends from the past. Maybe too heavily. But if Triple-A horror is dead or dying, does that matter?

A GUN WITH ONE BULLET

FAITH is a game of anachronisms. Its 8-bit computer aesthetic is unnerving when combined with the fluidity of its rotoscoped cutscenes, which is the main reason I picked it up in the first place. But I didn’t know how long this project had been in the works and how that goes someway to explaining its unique DNA. FAITH is separated into three chapters, the first released in 2017, during both the height of YouTube Lets Player influence and the endless Unity horror collectathons inspired by Slender. This might go some way to explain why FAITH plays the way it does- John, the tortured priest protagonist, moves at a molasses pace, and the principle collectables are notes, though these are not mandatory as in Slender et al., they are merely to add flavour text. Yet despite being somewhat beholden to the cliches of Youtube-friendly horror games with its convoluted lore and abstracted lo-fi gore, it’s not hard to see why FAITH stood out at the time and why it continues to do so now, with its final chapter releasing in 2022. Unlike the many Slender and Amnesia clones, there’s combat. John can wield his cross in one of four directions and cannot move while doing so. He faces all manner of demons, ghosts and other unspeakables throughout the game, their movement and abilities always outstripping his own.

FAITH is a horror game, but it is not a survival horror game. Barring extremely select circumstances, you have no resources to manage, no inventory, and no health. You cannot be more or less prepared for an encounter- you will always die in one hit. There are puzzles, but they can only be solved with observation and that one single cross interaction. Even when you briefly get a gun, John’s eerie text-to-speech voice informs you that it has “one bullet”. The mechanics are so stripped back that I worried they would outstay their welcome- each chapter is longer and more elaborate than the last, but aside from picking up an item now and then, your basic mode of interaction never changes. But everything else does. FAITH is a game of consistently inventive (and occasionally very cruel) setpieces. Some take obvious inspiration from horror films- a segment in which John is strapped to a hospital bed would be reminiscent of Jacob’s Ladder even without the cutscene that is almost a shot-for-shot recreation of its famous hospital scene. What helps this from feeling too egregious is that these influences are filtered through FAITH’s aesthetic and somewhat rudimentary gameplay; there's a charm in this playable rollercoaster ride of horror tropes. It does mean that the game suffers on replays, much like the aforementioned Resident Evil Village- a haunted house is less fun when you know the tricks. Compounding this is the multiple endings, with each chapter having a true ending with increasingly annoying requirements. Since I have a broken gamer brain, I naturally got all of these endings and achievements that barely have any consequence. That last part isn’t the game's fault, but asking players to redo an entire chapter is increasingly problematic when they only get longer. Chapter 1 doesn’t even force you to replay the whole game- all endings can be achieved from the final save point. 2 and 3 have fewer endings, seemingly to “fix” the problem of having to do things over too many times, and 3, in particular, adds more events (and recontextualises others) to reduce repetition- a welcome effort, but a solution to a problem of its own making.

Unfortunately, that isn’t where the problems end. It’s still a game I highly recommend, but the issues are easier to spot when a game is this straightforward. If I list each minor annoyance, there’s no way you’ll come away from this article thinking I like it- I do, I’m just picky, and harsher on the things I enjoy than the merely mediocre. It feels like it's lacking confidence. Baffling as a YouTube video describing FAITH as “just like Undertale” was, the leaning on referential and self-referential humour does feel similar to Toby Fox’s RPG, but we don’t yet have a superior written follow-up from Airdorf yet. The game isn’t badly written or constructed, but it tends to kneecap itself. Some of the scares would have been more effective without explanatory notes or graffiti, no doubt placed to make the game feel fairer. But why should horror always be fair? The difficulty of each chapter ending boss makes it clear that Airdorf doesn’t want to pull punches, but this over-explanatory tendency reminds me of that awful whiteboard in A Quiet Place. “WHAT IS THE WEAKNESS”? FAITH will be sure to tell you. I suppose it reduces frustration, and even some of the best horror games struggle to balance unnerving and frustrating. I won’t hold that fumble too much against FAITH. I do, however, take issue with the memes and other more obvious references. That brilliant hospital section I mentioned earlier has an abstracted version of the Ctrl+Alt+Del comic “Loss” on a curtain, right in the middle of a tense encounter. It’s a reference that only gets more obnoxious when you remember that this is FAITH Chapter 3, released mere months ago, a 2022 game that felt the need to prominently reference a bad webcomic from 2008. Less beating a dead horse and more that the horse is so dead that even its bones have turned to dust.

Perhaps this is unsurprising, given the publisher. Like several smaller publishers, New Blood relies heavily on memes and shitposting in their marketing. It’s a smart strategy- adding buttplug support to Ultrakill is certainly pretty dumb, but it’s the kind of dumb that invites incredulous quote retweets and, therefore, even more eyes on their product. It matters less how many Gabriel bodypillows they sell and more that there is probably someone who knows what Ultrakill is because of them. And so what? Ultrakill is excellent, and aside from one secret mission, it doesn’t feel like the meme branding affects anything in the game (yet- it’s still in early access). It takes itself seriously, not in a dour sense, but a confident one. In FAITH, however, if you wait at the end of the game's spectacular and somewhat emotional true ending, notes from Airdorf appear urging you to hurry up. I didn’t see this when I played; indeed, it got a laugh from the streamer I saw it from. I don’t want to be the fun police- a small fake-out in that final boss did make me laugh, and it didn’t feel detrimental. Nor did several other smaller nods to FAITH’s nature as a videogame, like John holding the crucifix above his head in the same manner as Link getting a new item. But not only are these small, snappy moments, they’re also not making a mockery of a serious moment. Waiting at that moment would actually be more likely to occur if you were emotionally invested in the scene, which is why it feels lacking in confidence. It isn’t everything, and I appreciate that such a thing will annoy many people less than it did me. FAITH still has such a unique vibe that I can’t help recommend it, but I hope Airdorf leaves it at chapter 3 and moves on to even better, bolder things.

GREAT HOLES SECRETLY ARE DIGGED

I first became aware of SIGNALIS during one of Steam’s “Next Fests”, a brief period in which Steam encourages devs to release time-limited demos. I played several horror games, from the grisly FPS Incision to the gruelling WW1-set horror of Conscript. SIGNALIS has more in common with the latter; it shares the same overhead camera with stylised low-poly character models, and is definitively a survival horror game, with all the limited inventory, save rooms and weaving between enemies that implies. Both also got off to a bad start- a reference to the old Resident Evil disclaimer, which I have seen on more indie games than Resident Evil games at this point. It makes me wonder if it would be best if developers were just slightly less fans of video games. In the case of SIGNALIS, the inclusion of numbers stations and The King in Yellow raised red flags- they’re not memes exactly, but certainly their relative popularity in online horror circles (and, of course, True Detective Season 1) had me wondering how much of its own flavour this game would have. However, I left the demo impressed- the presentation was and still is incredibly slick and impressive for such a small team, and as with Conscript it just felt good to be playing a real survival horror game again, looking like putting on an old pair of blood-spattered boots. The full release came, but I was midway through FAITH and, more importantly, moving back from China to the UK, so I didn’t actually play it until I settled back at home. I’d already heard some of the incredibly positive praise from friends and the press, so I was looking forward to a good time.

And I had one! SIGNALIS is a tremendously self-assured game, one that is confident enough in the strengths of its aesthetic and gameplay that it’s willing to leave you fumbling in the dark with regards to its story. There’s fun in piecing things together, through the sumptuous sprite work cutscenes to emails on old computers to the environment itself, a grim future world of cold aluminium and concrete, punctuated only by pulsating, rotten flesh. The inventory management is just on the right end of cruel (though limiting you to carrying one ammo stack per weapon did make some of my hoarding irritatingly useless for the final fight), as you only have six slots total, making it a more similar experience to playing RE1 Chris Redfield than Jill Valentine. It feels effortless, but given the effusive praise from uh, everyone, I hope you’ll indulge me in being a bit mean.

SIGNALIS is a game made by fans of survival horror games, and like with other fan works it perhaps takes more than it should, and doesn’t always improve (or take others improvements) on genre conventions out of stubbornly clinging to tradition. You can see this in particular with a lot of crowdfunded “spiritual successors”, though to SIGNALIS’s credit it isn’t just a Resident Evil tribute, it's more of a blend of influences. The pale, gangly anime androids with their black bangs and existentialism evoke Tsutomu Nihei’s BLAME!, and there's certainly an argument that Nier Automata has thematic influence, but really it is Silent Hill that SIGNALIS is most enamoured with. I’m not going to list every reference in some exhausting play by play, not just because that would be boring but also I don’t want to participate in that tiresome database animal activity of making sure everyone knows I got the reference. There are a lot. It and FAITH make the same very specific one- the looping holes of Silent Hill 2’s prison. Harmless enough, in either case, SH2 certainly didn’t invent their usage as a metaphor for mental descent, and holes take on a different significance within SIGNALIS’s narrative. Less forgivable is the near direct lifting of Nowhere.

Nowhere is a recurring segment in Silent Hill games, usually towards the end of the games. It is the epicentre of the town’s malevolent force, where reality breaks down even further, unmapped assemblies of rust, gore and impossible architecture. Entirely coincidentally, SIGNALIS also has an area where there’s even more gore and rust than the rest of the game, where you don’t have a map and doors take you to rooms at impossible angles. Lest you think that too subtle, it’s even called Nowhere in the game, which feels less self-assured and more overconfident. It’s especially irritating, given that it’s a mechanical highlight; I just wish it wasn’t wearing the skin of another game. Confidence or no, if you riff on the best, you will be compared against them. There are some things that SIGNALIS does better than classic survival horror games. The controls are more approachable, the boss fights (generally) more engaging and the puzzles are clever without being obtuse. But enemies aren’t memorable or threatening enough, the Resident Evil Remake's “burn the corpses, or they get back up” mechanic works less well in the relatively wide corridors of SIGNALIS, those smooth controls making it even easier to avoid enemies completely. Thankfully there’s Kolibri, an easy highlight of the bestiary, that requires an out-of-the-box solution to defeat. The moment I first saw one is amongst the game's most memorable, which is why it’s baffling that it makes the same mistake FAITH does by including a pamphlet explaining exactly how to solve this (not particularly difficult!) puzzle. It’s easier to miss than FAITH’s graffiti, and indeed I did miss it myself, but considering how little handholding most of the puzzles have, it's an odd and disappointing inclusion.

Keys are also something that SIGNALIS handles worse than Resident Evil. Playing as Chris in RE1 is an exercise in fussy inventory management since he just has six inventory slots compared to Jill’s eight, and he doesn’t benefit from her lockpick. That means more keys and key items required and endless traipses back and forth from save rooms. SIGNALIS doesn’t use Ink Ribbons, the consumable and finite resource required to save in classic RE games, and save rooms are more frequent, but key management is even fussier. Each key in RE1 opens several doors. Every key in SIGNALIS is single-use. This does at least mean it’s easier to remember which key opens where, but it also means there’s way way too many, and on more than one occasion, a key will just give you another key. Resident Evil does this too, but at least tries to be more subtle about it, i.e. a key opens a door that gives you a key item. It raises the question- if you’re going to borrow so heavily, why not borrow more of the things that worked? If it takes the Crimson Head mechanic from Resident Evil Remake, why not its map, that informs you if you haven’t collected everything in a room? It’s understandable not to point out every consumable (like the remakes for RE2 and 3), but given the visual style, it can be easy to miss a key item in the dark and then have to bounce between rooms. I’m not going to say all these issues are a death by a thousand cuts, and it’s still one of my favourites from 2022. It certainly handles having multiple endings better than FAITH, and there is something to be said for a brand-new, well-made survival horror game existing at all. I just wish the devs had gone further to transpose their fan interests into something less like a tribute and more of an evolution. A confident blend, sure, but a blend nonetheless.

WHEN WE ARE ALL MEAT AND WORMS

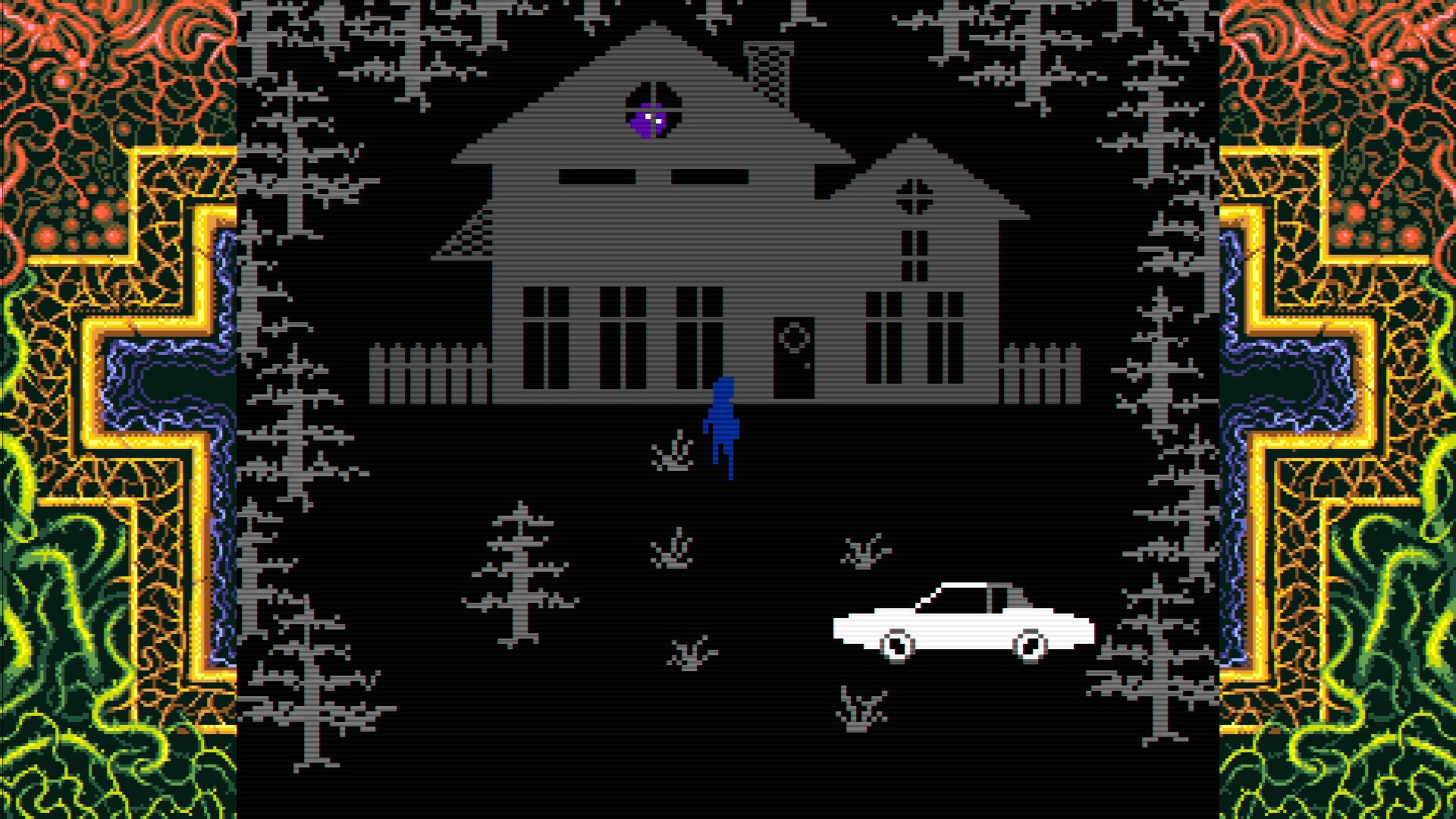

ATAMA could not be franker with its influences. “Inspired by Forbidden Siren and Junji Ito” is right on its Steam store page, and “inspired” might be putting it lightly. Forbidden Siren, or just Siren, is a series of PS2/3 stealth horror games with a unique central mechanic- you can “sightjack” your enemies, allowing you to see from their perspective. It’s a mechanic that’s useful (no MGS-style radar means its needed as an alternative), tense (the zombie-like Shibito often have quite disturbing routines, and there’s always the fear of seeing yourself from their eyes) and disorientating (constantly flipping perspectives very quickly erodes your spatial awareness). ATAMA lifts it wholesale, the only difference being that it maintains a first-person perspective even when you aren’t sightjacking. It’s what you’re running from that’s inspired by Junji Ito- ATAMA’s rotting mining village is haunted by giant, floating heads, inspired by Ito’s “The Hanging Balloons”. Biases on the table- that’s my favourite Ito short, and the team behind ATAMA is headed up by Michael Sawyer, better known as Slowbeef, whose work I’ve followed online for a number of years that I really don’t want to think about. If I seem kinder to ATAMA than SIGNALIS, that’s part of it (as is good old-fashioned contrarianism brain), but there are other reasons.

ATAMA is, for lack of a better word, charming. It’s a scrappier game than FAITH and SIGNALIS and one that’s considerably shorter to complete. That probably works in its favour- you don’t have a chance to get sick of anything, and the flaws that are present don’t stick around for long. Though the basics mechanics don’t change (much), each segment adds a wrinkle to the formula, and the positioning, number and behaviours of the roaming heads only get crueller. It’s the only one of these games that scared me- the heads themselves have uncanny designs, and they make ungodly sounds on seeing you, immediately breaking from their routine to devour you. I don’t think that’s a useful metric for determining how “good” any piece of horror media is, but ATAMA is an incredibly efficient machine for tension, one that, after running me ragged through a far too-open road through the town, delighted in showing me this immediately after:

It’s not really a survival horror game- it has more in common with the no-combat Unity engine chase-em-ups of the 2010s. Perhaps that’s what makes me more critical of SIGNALIS- those Unity games aren’t my preferred horror experience, so if you make something that is, I will find it comforting, sure, but you’re going to be compared to Resident Evil and Silent Hill, elevated as they are by nostalgia. FAITH and ATAMA have the luxury of being more unfamiliar, despite also being heavily influenced by the horror of the past. ATAMA’s production fascinates me, too- there are original assets created for the game (the heads being the highlight), but a lot of the environments are constructed from pre-made assets from many, many different sources. Aside from some odd bits of decor, I hadn’t noticed anything “off”, nor did I know just how many assets were used until the credits rolled. I kind of admire the transparency- each asset is given as much credit space as the people who worked on it, and the team did a great job cohering all these disparate 3D models into a distinctive art style. That’s the strength of the game in general- despite how blatant the influences are, it feels unique- it may also help that there are only three Forbidden Siren games, all three being a bit rough to go back to. It does have its issues- the true ending is a bit annoying to get, and if you don’t go out of your way to get the necessary collectables it can be easy to cheese your way through some sections, but as with the other two games I do highly recommend you try it.

I don’t want to rank these games against each other, as they’re very different slices of horror. FAITH is one of the most aesthetically unique games I’ve played in a long time, and its commitment to experimenting with its simple formula is remarkable. SIGNALIS deserves much of the praise (and hopefully sales) it gets, and considering the complexity of its design and its small team, it’s a true miracle that it feels as polished and self-assured as it does. ATAMA seems to have gone more under the radar, which is a shame because what it does with relatively little is extremely impressive. All three borrow heavily from horror games of the past. Why does it matter? If the series they’re borrowing from aren’t dead, their modern iterations are so drastically different from what these games are riffing on. They’re standing on the shoulders of giants, but the giants are dead. Perhaps that’s why the reference and reverence sometimes bother me- they’re dead for a reason, and it isn’t just because Konami and the like are assholes. There are so many Resident Evil games in that classic style that still hold up (there’s also Code Veronica and Zero), but they and the countless other survival horror games on the PS1 and 2 are the reason Resident Evil 4 ended up being such a breath of fresh air, and why the muddled American Silent Hill games didn’t catch on. Resident Evil has had to bend back to the past after burning out 4’s more action horror formula, but that too has had mixed results. It’s understandable why some indie games go for nostalgia- it's a great way to market your game, especially when your name isn’t yet established. Despite FAITH, SIGNALIS and ATAMA being well worth your time, they all represent the chance for even better successors, hopefully, ones less beholden to the past. There’s already fatigue setting in with the swath of indie “boomer shooters” that lean closer to DOOM and QUAKE- there’s only so much space on those dead shoulders. At some point, you have to take more of a leap, and I hope that all three have had enough success for them to do so. If you still don’t think it matters that these games borrow heavily from the past, then you’ll likely enjoy them even more than I do- it's a philosophical distinction, not one I can or want to convince you of.

But if the reports of triple-A horrors death aren’t exaggerated, then I hope we can start building giants of our own.